[ad_1]

GEOPOLITICS waits for no man, not even the United States’ president-elect. Little more than a week after Donald Trump’s victory, Xi Jinping, president of the world’s second-largest economy, set off for Latin America—his third trip there since 2013—clutching a sheaf of trade deals. They were proposed long before the change of government in Washington. But at a time when the image of the big, bad yanqui seems to be making a comeback, Mr Xi may find himself with an opportunity to boost Chinese influence in the American backyard.

China’s aims in the region are expansive. In 2015 it signed a slew of agreements with Latin American countries promising to double bilateral trade to $500bn within ten years and to increase the total stock of investment between them from $85bn-100bn to $250bn. China also wants good relations in order to diversify its sources of energy, to find new markets for its infrastructure companies and to project power, both soft and military, in the western hemisphere.

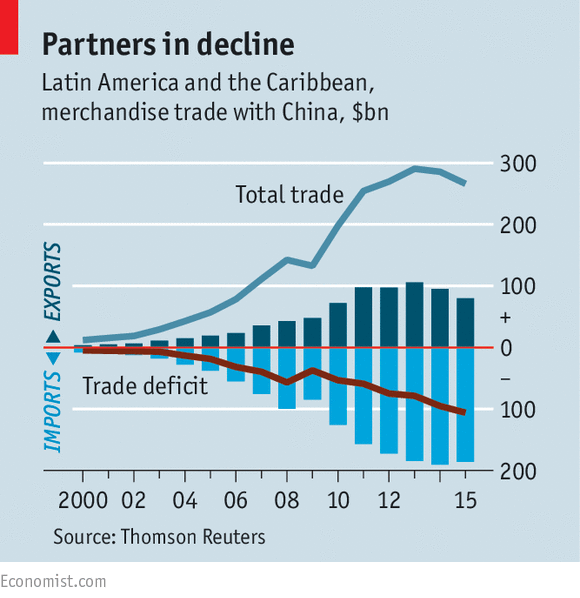

But Mr Xi, whose itinerary takes him to Ecuador, Peru and Chile, will have to work hard for these gains. After a long period of rising trade and closer relations, many Latin American countries are having second thoughts about their embrace of China. Exports from the region (plus the Caribbean) shrank last year, largely because Chinese economic growth slowed. China’s exports fell by less, so Latin America’s trade deficit with the country increased (see chart).

Four raw materials—copper, iron, oil and soyabeans—account for three-quarters of the region’s exports to China, a greater share than they do of trade with the rest of the world. But the impact on employment is slight. A study by Boston University found that trade with China generated 17% fewer jobs per dollar’s-worth of exports than did trade with other countries.

Almost all imports from China are cheap manufactures. Some Latin American economists argue that Chinese subsidies to their producers undermine domestic industries. A new study published by the Atlantic Council, a think-tank in Washington, concludes that Chinese exports “have had an effect on the region’s deindustrialisation”. As for China’s push to invest in infrastructure and natural resources, “that won’t give us the quality jobs we need,” said Rebecca Grynspan, the secretary-general of the Ibero-American Community, which comprises Spain, Portugal and Latin America, at a seminar in Santiago last week.

As Latin American expectations are changing, so too is the pattern of Chinese investment. In 2010-13, 90% of it went to natural resources. Recent investments have branched out. In September this year China’s State Grid bought a 23% stake in CPFL, a Brazilian energy utility, for $1.8bn. WTorre, a Brazilian construction company, signed a deal with China Communications and Construction Company International to build a port in Maranhão, a north-eastern state. Chinese financial firms are getting involved. Fosun, an investment company, recently bought a controlling stake in Rio Bravo, an asset manager in São Paulo. Last year Bank of Communications bought 80% of BBM, a Brazilian lender, for 525m reais ($174m).

China has its own reasons for wanting change. Many of its biggest trade deals have been with left-wing governments, which initially saw China as an anti-imperialist sugar daddy. Chinese loans over the past decade have fed that expectation. They went mainly to four countries that had left-leaning governments for most of the period: Venezuela, Brazil, Argentina and Ecuador. Now China worries that bankrupt Venezuela, which hews doggedly to self-destructive populism, may not repay its debts. And it wants to improve its standing with new, business-friendly governments in Argentina and Brazil.

To dispel the notion that it is mainly a friend of the left, China is offering free-trade agreements (FTAs) with more open economies. It already has such deals with Peru, Chile and Costa Rica. Last year China’s prime minister, Li Keqiang, went to Colombia to talk about one. On his trip this month Mr Xi wants to expand the FTA that China signed with Chile in 2005. In October Uruguay’s president, Tabaré Vázquez, went to China to talk about an FTA. That prompted the other members of Mercosur, a four-nation trading block led by Brazil, to consider joint efforts to reach a group-wide trade agreement with China.

The death of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), from which Mr Trump has said he will withdraw, may also prove an opportunity. China is hoping to use a meeting in Peru of 21 Pacific Rim economies to boost the prospects of its TPP-alternative, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, which includes India and Japan, but not the United States.

Luckily for China, Latin America’s recent turn to the political centre implies greater pragmatism rather than hostility to the People’s Republic. It has made Brazil and Argentina more open to trade and investment, reckons Alicia Bárcena, the head of the UN’s Economic Commission for Latin America. “So if the Chinese are ready to invest, it should be easier for them.”

Mr Xi is not just interested in commerce. In his speech to Brazil’s congress in 2014 he talked about a new “strategic partnership”. This time, says Oliver Stuenkel of Fundação Getulio Vargas, a Brazilian university, Mr Xi “will project himself as a stabiliser”, which will do no harm when many leaders are fearful about what a Trump presidency might bring.

Chinese experts on Latin America scoff at the notion that China has geopolitical interests there. But it is hard to believe that it does not welcome the idea of having friends in the United States’ historical sphere of influence to match America’s allies in East and South-East Asia. A bonus is that 12 of Taiwan’s 22 allies are in Latin America and the Caribbean. So good relations between China and the region could chip away at Taiwan’s claim to some form of independent status.

In 2015, the government of Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, then president of Argentina, signed a $1bn agreement to buy Chinese fighter jets and ocean-going patrol vessels. The agreement took China’s arms sales on the continent into a new league (until then, except in Venezuela, they had been mostly small scale). She also approved a deal giving the Chinese the right to build a satellite-tracking station in Argentina. After criticising the arrangement before his election in November 2015, the new president, Mauricio Macri, has given it the go-ahead.

The base is in Neuquén province in Patagonia. Yu Xueming, the project’s manager, says the site has no military purpose and is designed as part of a lunar mission to be launched in 2017. But satellite experts say its parabolic antennae could have military uses, too. The facility’s operator is a unit of the People’s Liberation Army, the name for all of China’s military services. The site is due to become operational next March.

China, it seems, is in Latin America for the long haul. And while it is there, it can keep one eye on the neighbouring giant to the north.

[ad_2]

fuente